Hot Town, Summer in the City

Chicago is one of the things that is some of all of me; it floats in my memory and lives in my bones.

I grew up on the south side and wear my growing up time like a badge of honor. I haven’t lived there for 35 years, but when people ask me today where I come from, without hesitation, I say, “Chicago.”

In the early 1960′s I was a five year old living at 5224 So. Albany. We had our neighborhoods back then and we had the Chicago Democratic machine. Everyone knew where everyone else belonged by their thick accents or their skin color. It was normal everyday thinking to think: the Italians are over here and the Pollocks are over there and the Spics are everywhere and the Blacks keep over where they belong, and watch out for those crazy Irish. I’m not saying this is right; I’m saying this is how it was. Most of the children I played with spoke English at school and a second language at home.

There was a bar on almost every corner with a bright, white and blue Hamm’s Beer sign that flickered in time to the tunes rolling out the door from the juke box. Steady traffic. I remember a bar called “The Ace of Clubs” and still think that if I ever owned one, that would be what I called it. If our parents weren’t down at the corner bar (and mine weren’t) they would be sitting on the front porch steps on any given July evening, cooling off with a Tupperware glass of ice tea, Tab, or Coca-Cola which was chilled with ice freed from a metal ice cube tray.

There was a bar on almost every corner with a bright, white and blue Hamm’s Beer sign that flickered in time to the tunes rolling out the door from the juke box. Steady traffic. I remember a bar called “The Ace of Clubs” and still think that if I ever owned one, that would be what I called it. If our parents weren’t down at the corner bar (and mine weren’t) they would be sitting on the front porch steps on any given July evening, cooling off with a Tupperware glass of ice tea, Tab, or Coca-Cola which was chilled with ice freed from a metal ice cube tray.  We learned to grab those frozen metal trays from the freezer with dry hands or get a freezer burn. Then we ran water over them to loosen the ice so the metal pull would crack the bricks free much easier. We never ran out of ice. We kept four trays going and the house rule was that if you took the last ice cube in a tray, you had to fill the empty tray and then slide it carefully (harder than it sounds) on top of the other trays. OR ELSE.

We learned to grab those frozen metal trays from the freezer with dry hands or get a freezer burn. Then we ran water over them to loosen the ice so the metal pull would crack the bricks free much easier. We never ran out of ice. We kept four trays going and the house rule was that if you took the last ice cube in a tray, you had to fill the empty tray and then slide it carefully (harder than it sounds) on top of the other trays. OR ELSE.

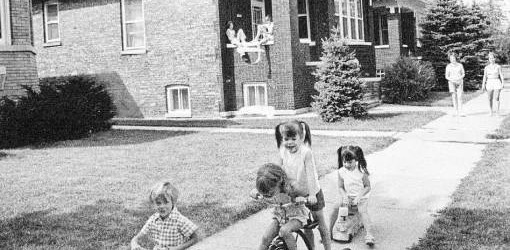

Summer evenings were a time when we came outside after filling up on meatloaf and mashed potatoes and canned corn and after sharing stories about our day and what Joey down the block did and what Suzy said about Mary Jo and we gawked over the new Chevy Impala with the big red fins and electric windows that the guy across the street got. The house would be all hot inside from the cooking and the breeze outside was welcoming under the setting sun. My dad usually wore his Dickies and a white tee shirt. Sometimes his pack of smokes would be rolled up in the sleeve. God, he was cool. Mom wore capri pants and sleeveless, jewel neck cotton blouses. We kids were all mix and match and hand me downs.

Parents would sit on painted porches, cement steps, or brick stoops talking about grown up stuff and shooing off the curious youngsters that were eavesdropping. We learned a lot about life from hiding under the front porch steps. It seemed to us, though, that most parents just wanted to get down to the bottom of the neighborhood troublemakers that day. A troublemaker could be a kid who stepped on Mrs. Stikovich’s flowers, broke a window with a baseball, or got caught riding his bike in the street. We all got in trouble for something now and again and our parents always found out. If a neighbor caught us, we’d catch it from them first and then they would tell our parents and we would get it twice as bad when we got home. Our butts were fair game for spankings whether we needed them or not.

Parents would sit on painted porches, cement steps, or brick stoops talking about grown up stuff and shooing off the curious youngsters that were eavesdropping. We learned a lot about life from hiding under the front porch steps. It seemed to us, though, that most parents just wanted to get down to the bottom of the neighborhood troublemakers that day. A troublemaker could be a kid who stepped on Mrs. Stikovich’s flowers, broke a window with a baseball, or got caught riding his bike in the street. We all got in trouble for something now and again and our parents always found out. If a neighbor caught us, we’d catch it from them first and then they would tell our parents and we would get it twice as bad when we got home. Our butts were fair game for spankings whether we needed them or not.

Eventually one of the parents would ask if anyone wanted an impromptu snack–usually one dripping with mustard, relish and onions. The hot dog joint was right up the street so we’d run in the house to get a scratch pad of paper and take down all the orders. If it wasn’t hot dogs, it was hamburgers from the G.I. Grill on Central. A couple of us kids would get assigned the mission to bring ‘em home hot and we might get a quarter out of the whole deal.

Eventually one of the parents would ask if anyone wanted an impromptu snack–usually one dripping with mustard, relish and onions. The hot dog joint was right up the street so we’d run in the house to get a scratch pad of paper and take down all the orders. If it wasn’t hot dogs, it was hamburgers from the G.I. Grill on Central. A couple of us kids would get assigned the mission to bring ‘em home hot and we might get a quarter out of the whole deal.

I have memory of a Dicken’s style vegetable man who would come clip-clopping down the side streets with his old wagon. It was pulled by two big, grey draft horses. He would sell tomatoes and onions right off of his cart and I remember it being an ancient, old and odd thing to see even back then, in 1966. Dr. Francisco made house calls if we were really sick and his office was up a large flight of narrow wooden stairs, above the Rexall Drug Store on Kedzie. My mom would call him after she had run out of cotton balls and cod liver oil to heat up on a spoon and pour in my ears. I had the mumps and the measles, there too.

Metal milk boxes sat on our porches, in the shade, and the Home Juice Company man would come once a week and leave two glass bottles of cold orange-pineapple juice. He sold other kinds, but we always got that kind. All at once folks everywhere would stop what they were doing and listen to see if “it really was the ice cream man coming.”  Quarters, dimes and nickles fell from pockets as we lined up and elbowed our way to 35 cent ice cream bars. Candy bars were 25 cents and you could buy a candy cigarette that puffed “smoke” for a penny at Lottie’s corner store. Lottie’s was where I ate my FIRST Dorito chip.

Quarters, dimes and nickles fell from pockets as we lined up and elbowed our way to 35 cent ice cream bars. Candy bars were 25 cents and you could buy a candy cigarette that puffed “smoke” for a penny at Lottie’s corner store. Lottie’s was where I ate my FIRST Dorito chip.

The very best thing that could happen to a kid in Chicago on a 90 degree day under a relentless sun that produced waves of visual distortion over the frying, baking, and sizzling pavement was when somebody’s big brother or uncle produced a monkey wrench. That wrench was magic. It could open up fire hydrants. It only happened once or twice a summer and when it did, people came from 12 blocks square. There would be 100 people running through the water gushes in the street and the force of the hydrant created ripples and waves that we could race our bikes through (if we were lucky and made it!) We would run and splash and scream and laugh and push and shove and cool off until we heard the sirens. The cops always found out. I’m not one hundred percent sure, but I think it was probably Mrs. Stikovich, avenging her petunias, who called them.

The very best thing that could happen to a kid in Chicago on a 90 degree day under a relentless sun that produced waves of visual distortion over the frying, baking, and sizzling pavement was when somebody’s big brother or uncle produced a monkey wrench. That wrench was magic. It could open up fire hydrants. It only happened once or twice a summer and when it did, people came from 12 blocks square. There would be 100 people running through the water gushes in the street and the force of the hydrant created ripples and waves that we could race our bikes through (if we were lucky and made it!) We would run and splash and scream and laugh and push and shove and cool off until we heard the sirens. The cops always found out. I’m not one hundred percent sure, but I think it was probably Mrs. Stikovich, avenging her petunias, who called them.

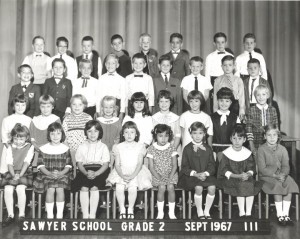

(me, sitting, 2nd from right side)

Dairy Air

Dairy Air